Sen. Joe Manchin pushes a sweeping pro-union labor law one step closer to reality

- Share via

Sen. Joe Manchin, widely regarded as a crucial swing vote in the narrowly Democratic Senate, moved a sweeping pro-union law one step closer to enactment Monday by declaring that he would become a co-sponsor.

The measure is the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, or PRO Act, which passed the Democratic House in March by a 225-206 vote, with one Democrat in opposition and five Republicans in support. It’s also endorsed by President Biden.

The PRO Act would be the most important law protecting worker rights since the original National Labor Relations Act of 1935.

We like driving the car and we’re not going to give the steering wheel to anybody but us.

— Then-Walmart CEO Lee Scott attacks a pro-union Congressional proposal in 2008

Among other features, it would overturn numerous provisions of the most important anti-union law in American history, the Taft-Hartley Act, which was passed by a Republican-controlled Congress over President Truman’s veto in 1947.

Manchin’s announcement, which came at an event sponsored by the United Mine Workers of America, doesn’t ensure passage of the PRO Act by any means.

Several of his fellow Democrats haven’t yet signed on to the bill, including Mark Warner of Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly of Arizona. That means the measure isn’t assured of a simple majority vote; a filibuster by Republicans would drive the last nail into its coffin. But Manchin’s support could place pressure on the Democratic holdouts to fall into line.

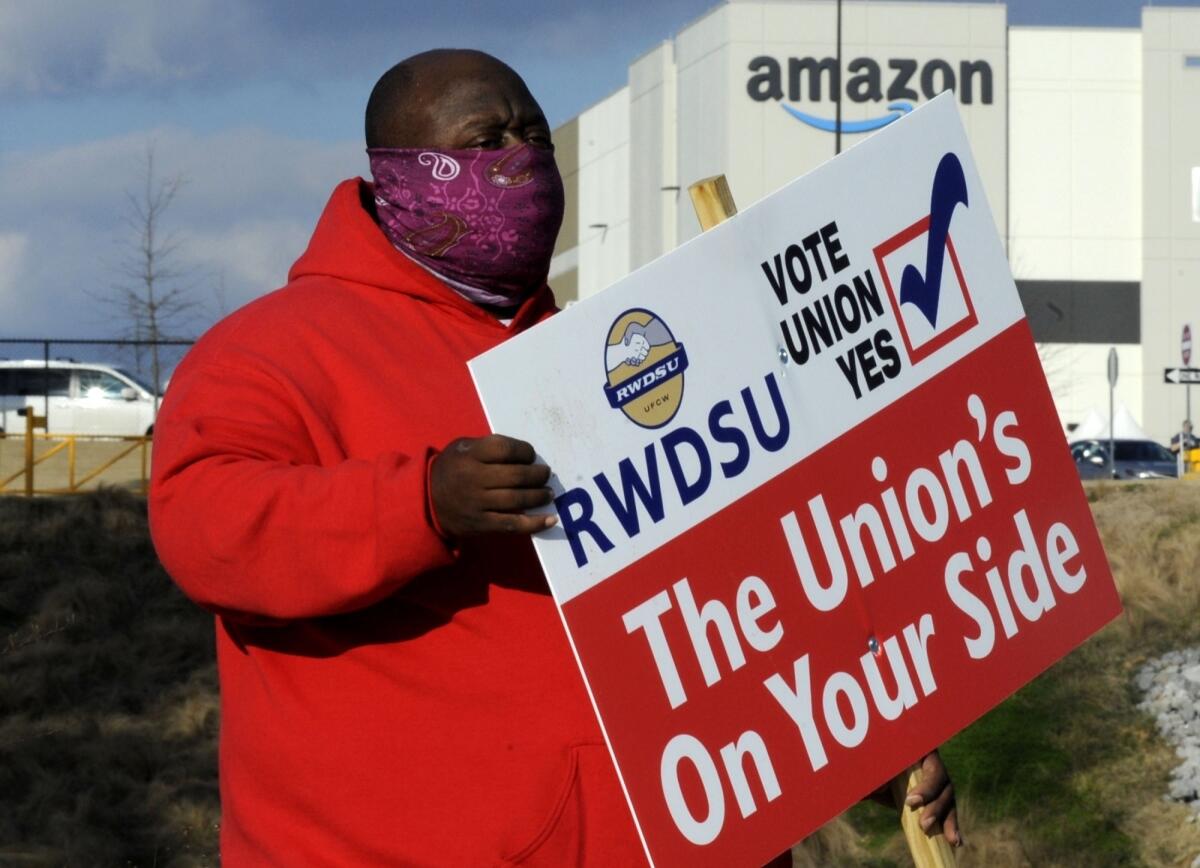

Amazon’s campaign against a union drive in Alabama has drawn fire from President Biden.

Nor is Manchin’s support all that much of a surprise. He has long been an ally of the mine workers union, which anointed him an honorary member last year. But he hadn’t explicitly endorsed the PRO Act until now.

That gives us an opportunity to examine the history of federal labor law and how it has allowed employers to run roughshod over unionization drives during the last three-quarters of a century.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

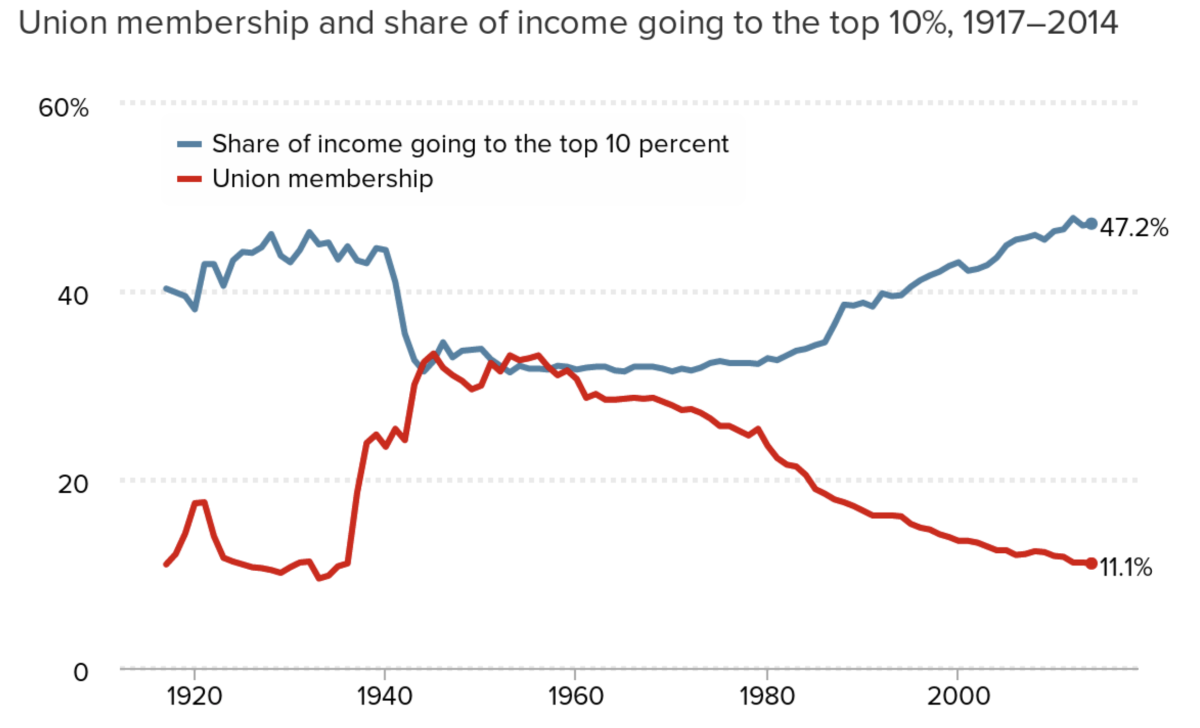

That’s a period that has seen a historic decline in union membership in the private sector from an estimated 36% in 1945 to 6.3% in 2020 (the government didn’t start keeping comparable statistics until 1983). So it’s reasonable to conclude that federal law played an important role in the decline.

Let’s start by describing the PRO Act.

The measure would ban a whole sheaf of actions used by employers to interfere with union organizing. These include “captive” meetings featuring anti-union propaganda, which workers are required to attend; firing workers engaged in union organizing; and misclassifying employees as independent contractors to deprive them of unionization rights.

The act would overturn the right-to-work laws in force in 28 states. The laws require unions to represent all employees in a unionized workplace without requiring them to pay union dues.

Such laws are a cynical stratagem aimed at depriving unions of resources. Typically, unions are required to represent all employees on a shop floor. They can charge dues to cover their expenses in negotiating contracts and bringing employee grievances, even for nonmembers.

Right-to-work laws require unions to perform those services without charging dues to nonmembers, even though the latter benefit from union services. That creates what’s known as a “free rider” problem — the unions are providing those services for free.

It would also outlaw forced arbitration of workplace issues or agreements requiring workers to give up their rights to launch class-action litigation in those cases.

The act would also codify into law the National Labor Relations Board’s 2015 Browning-Ferris decision, which rejected that company’s assertion that workers at its Milpitas landfill in Santa Clara County were actually employees of a recruitment firm, and thus weren’t subject to a Browning-Ferris labor contract.

The NLRB ruled that Browning-Ferris exercised so much control over the wages and working conditions of the workforce that it stood as a joint employer.

The Trump-dominated NLRB overturned the Browning-Ferris decision last year, allowing employers to dodge their responsibilities to their workers by hiding behind a labor contracting firm.

Proposition 22 is a revolutionary step in the influence of tech-based businesses in our daily lives in general and the lives of workers in particular.

Under the PRO Act, workers organizing a union would have the right to choose their own location or mode of a union election, whether electronically or at a location off the employer premises. This would block employer coercion of voters.

How important is that provision? One can judge by the efforts Amazon made to force employees at its Bessemer, Ala., warehouse to conduct their recent unionization vote at the warehouse in person, despite the threat to voters’ health from the pandemic. The National Labor Relations Board rejected the company’s offer to provide a tent on a parking lot for the vote, and mandated that the vote be conducted by mail.

Amazon, incidentally, made vigorous use of captive meetings and papered the facility with anti-union messages. (For reasons still being debated by labor experts, the union lost the vote by a wide margin.)

Finally, the PRO Act would streamline union elections and give newly unionized companies a tight deadline to negotiate and reach an initial contract, or go to mediation.

The PRO Act “would make most of what Amazon did in its Alabama anti-union campaign illegal,” labor historian Erik Loomis told me. He called it “the most important piece of labor law to support workers since the Fair Labor Standards Act” of 1938, which established the right to a minimum wage and overtime pay. “It’s a necessary step toward building unions back up in this country again.”

The PRO Act is the heir to the last major union-friendly legislation considered by Congress. That was the Employee Free Choice Act, over which a major battle was fought in 2008 and 2009.

The business lobby attacked the EFCA by focusing on a provision known as card check. That rule would have required employers to recognize a union supported by more than 50% of its workers through signed cards, without requiring workers to conduct a lengthy and expensive secret ballot.

Employers’ gratitude for their ‘hero’ workers didn’t last long

Employers shed crocodile tears over the loss of ballot secrecy, arguing that card check would enable labor organizers to harass workers into supporting unionization.

This was never an especially credible argument. As Gordon Lafer, a labor policy expert at the University of Oregon, observed, under the secret ballot system management had free rein to harass and coerce employees into rejecting the union.

“When workers are asked to sign a statement supporting unionization,” Lafer wrote in 2008, “they are overwhelmingly afraid not of the pro-union fellow employees whom they have seen harassed and ostracized ... , but of the wrath of anti-union managers.”

The most explicit complaint about the EFCA came from Walmart’s then-chief executive, Lee Scott, during a conference call with Wall Street analysts in October 2008. “We like driving the car and we’re not going to give the steering wheel to anybody but us,” he said.

Supporters eventually removed the card check provision from the EFCA, but the bill failed anyway.

In union organizing today — like then — management holds almost all the cards. One recent anti-labor screed by the Pennsylvania law firm McNees Wallace & Nurick, headlined “Why the Protecting the Right to Organize Act (PRO Act) Keeps Us Awake at Night,” lamented that it would “significantly upset the balance of power between employers and labor unions” — as if the relationship between them were at all balanced today.

The PRO Act won’t solve all of labor’s problems. The Bessemer vote, which went overwhelmingly against the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, shows that organizers need to find new strategies, especially in the lightly unionized Southeast. But the measure would take employers’ and governments’ thumbs off the scale in labor-management relations, and that’s a start.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.